“The Death Tour” is ready to pound the mat at the 2024 Slamdance Film Festival.

The documentary about an annual, professional wrestling excursion through Canada’s northern territories, organized by promoter Tony Condello for more than three decades, has been selected for the festival’s Documentary Features category, and co-director Stephan Peterson is honored.

“This has exceeded our expectations,” Peterson said. “This project started a long time ago, it’s still kind of sinking in. I think it will hit us when we’re in Park City.”

Sonya Ballantuyne, the film’s other co-director concurs.

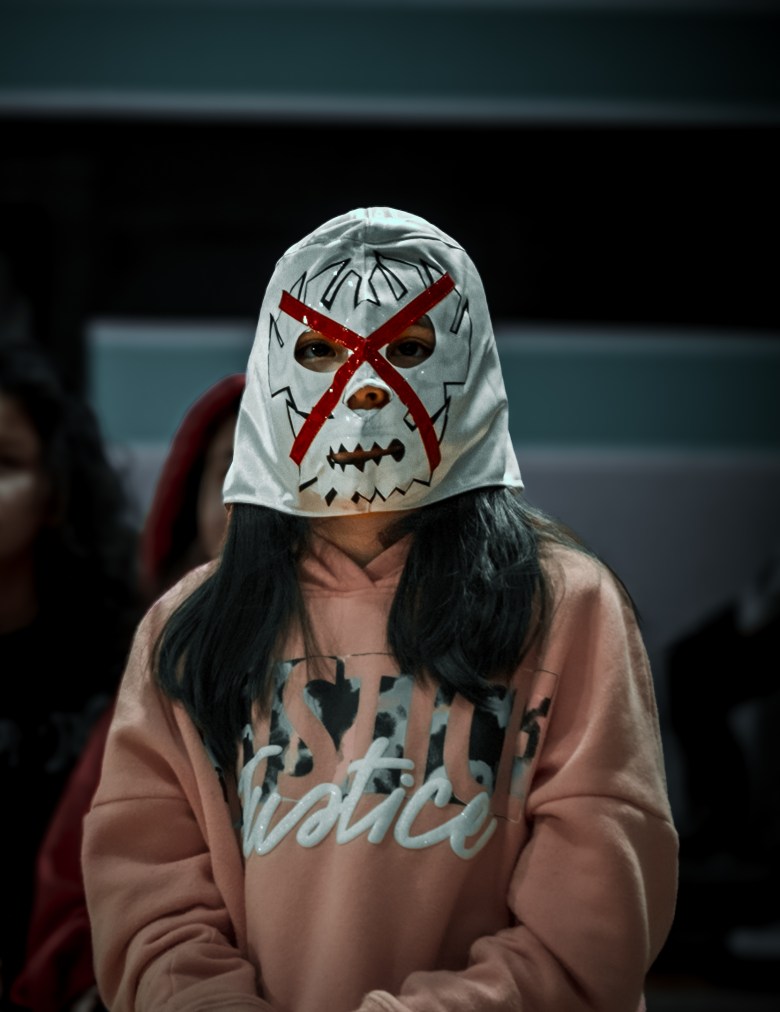

“I have always been a wrestling fan, and I’ve been aware of the bold opinion people have about wrestling,” she said. “So every single time people have gotten word about it going to Cannes and Slamdance, it’s been amazing to see how people have embraced it. I’m very happy to see how this little thing we created is going so far.”

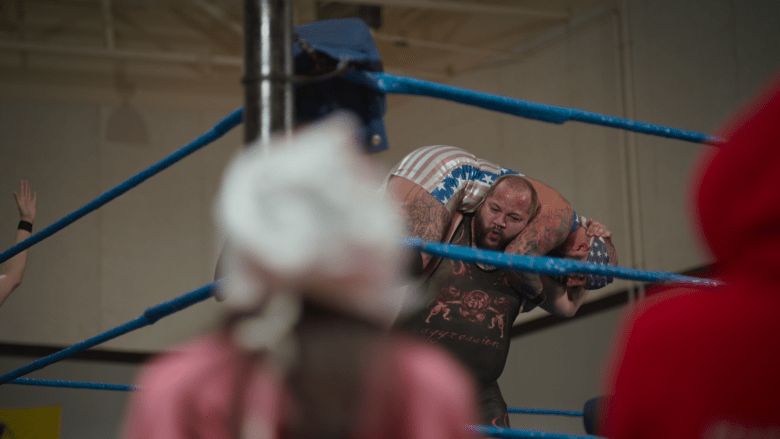

The film is a road-trip documentary that follows professional wrestlers during The Canadian Death Tour, a 15-day stretch as they bring joy, fun, performances and hope to indigenous communities.

Peterson, who didn’t grow up a wrestling fan, got an eyeful of the tour nearly six years ago.

He was on another assignment in a small town in central Manitoba, and the only big buildings there were schools and a community center that also served as gymnasium.

“This one night the kids all just swarmed at the local gym and when we asked what was going on, they all said, ‘Wrestling is coming to town,'” he said. “We decided to buy tickets and seeing this traveling circus known as The Death Tour come to town was the last thing we expected. It was crazy seeing this wild spectacle of adults all greased up doing death-defying stunts for these kids who were totally enthralled with what was going on.”

Peterson decided to do some deep-dive research and found that The Death Tour, also known as the Northern Hell Tour, is a piece of wrestling lore, where some wrestlers hope to gain exposure, and others on the twilight of their careers only want a final chance to hear the roars of adoring crowds.

“I decided I wanted to do a documentary about it,” he said.

Since Peterson didn’t have a background in wrestling, he reached out to Ballantyne, who not only loves wrestling, but is also a Swampy Cree writer and filmmaker from the Misipawistik Cree Nation in Northern Manitoba.

“I came on with Steph’s asking, because he noticed how much this focused on the indigenous side,” she said. “The Tour has, more or less, always gone to the same reserves, and while every wrestling fan knows about it, nobody really knows why it happens and why it goes to these communities.”

While there have been other documentaries that focused primarily on the tour itself, Peterson and Ballantyne wanted to focus the tour’s impact on the communities it visits.

“I encountered the tour when I was a child, and while the documentary is about wrestling, it’s not all about wrestling,” Ballantyne said.

One of the things Ballantyne discovered during principal photography was how the tour literally saved the participating wrestlers.

“Every single wrestler we spoke to had their own reasons why they came into wrestling and it was always about something bad that had happened to them,” she said.

Some of those common themes included loss of family members and substance abuse, Ballantyne said.

“It was sobering, but I had never seen that level of commitment of something that wasn’t going to give you a lot back, except maybe for the adoration of the kids,” she said. “To see that end of the spectrum, where they would push through because they love something, was something eye opening to me.”

During the filming, Peterson realized The Death Tour also brought hope to the communities during the most isolating time of the year.

“We would go to schools and get mobbed by kids,” he said. “In fact, the kids were almost as interested in what we were doing almost as much as they were in the wrestlers.”

Still, depression and the feeling of hopelessness is all too real in those communities, Peterson said.

“We knew there were suicide epidemics in these communities over the past four to five years, but then we started hearing about happenings in towns ahead of us while we were on the tour,” he said. “And to hear about what happened ahead or behind you was devastating.”

In one town that had experienced a suicide, the wrestlers didn’t know if anyone would show up, but the community did, Peterson said.

“So, what we decided to do was put together a website called Thelifetour.ca that lists a number of organizations that do a lot of physical health and mental health work with indigenous youths,” he said.

The film also touches on colonization, Ballantyne said.

“I grew up on a ‘reserve,’ and a lot of the ones we visited were what mine was like 20 years ago,” she said. “I thought because my reserve now had powwows and sun dances, I assumed everyone had gotten to that point. So it was sobering for me to find out that there were still communities that had these (oppressive) opinions about our history and culture.”

Still, there were kids in those communities who were interested in the culture, and that was due to one of the wrestlers, Sage “The Matriarch” Morin, who is also Cree, said Ballantyne.

“Sage sang a traditional song in one town, and she taught it to some of the kids,” Ballantyne said. “And when we left, she told them that when she came back the next year that she expected them to have the song memorized. So, it was interesting how this film may have instigated a small bit of change.”